The Colorful Legacy of Arnold Varga

Arnold Varga may not be a household name today, but his impact on advertising and illustration is undeniable. Working quietly from the basement of his mother’s house in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, Arnold revolutionized newspaper advertising with bold, colorful visuals that broke away from the black-and-white norm. Despite lacking formal art training and shying away from the spotlight, he earned national acclaim and awards year after year. Two years after his death, this unassuming creative genius was honored alongside legends like Walt Disney and Paul Rand with induction into the Art Directors Hall of Fame. This blog explores the life and legacy of a man who reshaped the way stories are told through images, all without ever developing a signature style.

Arnold Varga died on January 1, 1994, because no one knew the actual date. He was born on January 1, 1926, because no one knew the actual date.

He did some of his best work not in one of America’s great centers of communication but from the basement of his mother’s house in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Yet this unassuming man was, in his day, one of the most honored art directors, designers, and illustrators in the world.

Beginning in the late 1950s, he started creating advertising that was ahead of its time, and still feels contemporary by today’s standards.

He never had formal training in art (he flunked art in high school), yet his illustrations—and the ads in which they appeared—garnered multiple national awards year after year.

From all accounts, he was a man with a keen sense of humor, entertaining, and loved by his associates. Nevertheless, he lived his final days as a recluse, dying alone in a local hospital.

Two years after his death, he was inducted into the Art Directors Hall of Fame, joining the likes of Walt Disney, Saul Bass, Richard Avedon, Milton Glaser, and Paul Rand.

He had no signature style. His work wasn’t distinctive like Seymour Chwast’s or Milton Glaser’s. You couldn’t say, “Oh, that’s a Varga,” because he would do almost anything, in any style that felt appropriate.

His former artist’s representative, Darwin Bahm, says Arnold was very picky about what he would work on:

Darwin: “Working with Arnold was never going to make you rich. I had a job from a client that was going to pay $3,000. I also had one for the Boy Scouts that was to pay $200. Arnold turned down the higher-paying job to work on the Boy Scout illustration because he thought the Boy Scout illustration had more potential. I made $62.75 commission off the job.”

In 1968, his artwork was displayed in an exhibition at the Carnegie Institute of Fine Art—the only illustrator ever so honored in the history of the museum. He also had a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

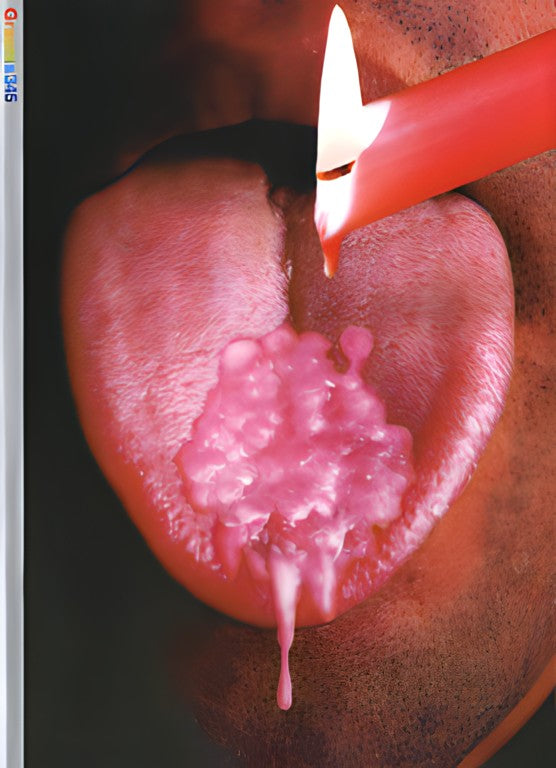

Before Arnold, most newspaper ads for stores looked like this:

Arnold created newspaper ads for stores that looked like this—bold, colorful, visually driven, not in black and white, but in vibrant color:

Instead of working with writers, writers worked with him, writing copy to fit what he thought should be the visual.

Ray Werner is a former copywriter living in Pittsburgh. He worked with Arnold on a number of newspaper ads for Joseph Horne, a local Pittsburgh department store.

Ray: “He was unpredictable; he would call you at any time and say, ‘I’ve got an idea for an ad.’ And of course you’d be okay with that, because you knew coming from Arnold it would be a really good ad.”

Arnold Varga approached advertising as a personal art form. In spite of the fact that he had almost no serious art training and conducted nearly all of his professional life within a few miles of his hometown, McKeesport, Pennsylvania, Arnold gained international recognition and was honored with eleven gold medals from the Art Directors Club of New York. Photographer Duane Michals, a childhood friend, says with some wonder, “He worked in this little steel town, without any real nurturing, and he bloomed into a major talent. He made it happen on his own energy.” Unknown to most, a further obstacle Arnold had to overcome was near-blindness in one eye and poor vision in the other.

The second of three sons, Arnold was born to Hungarian immigrants who had little formal schooling. His father, Sigmund Wargo (Varga adopted the spelling closest to the original pronunciation of “Wargo” for his professional name), worked in the local steel mill, but he died when Arnold was ten years old. His mother, Julia, had artistic leanings, expressing them in the decoration of her home and in her encouragement of her children. Robert, Arnold’s elder brother by four years, was the designated family artist, though he earned his living at the mill until he was killed in an accident there at age twenty-four.

Arnold first drew attention from his grade school teachers when, at the age of twelve, he executed a clay bust of Abraham Lincoln. This led the McKeesport Optimist Club to sponsor him for Saturday art instruction at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). Arnold also attended summer art sessions there, as the only child in the class. “I was the big joke of the department,” he once commented. In 1945, following his graduation from McKeesport High School—where he somehow flunked art—Arnold took a six-month course at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh. These experiences were the sum of his formal art education.

At eighteen, Arnold began freelancing for Cox’s department store in McKeesport. He went in one afternoon to show some drawings to the owner, Robert Cox, and was sent home with an armful of black dresses to sketch for the next day’s newspaper ads. (Arnold pressed his younger brother, Art, into service as his model for the job.) He would also walk into local shoe stores, usually coming out with some illustration assignments.

Commuting to Pittsburgh, Arnold started as a messenger for the Joseph Horne Company but quickly worked his way into its advertising department. By the early 1950s, the Sterling Linder Davis store lured him to Cleveland, Ohio—150 miles from home—to head their advertising department. Devoted to his mother, Arnold returned home in 1953 when the Korean War drew Art into the army. There, he was invited to join the Pittsburgh branch of Ketchum, MacLeod & Grove, Inc., as creative art supervisor, working on various national accounts, among them Alcoa, Talon Zipper, and Rubbermaid. Arnold later moved to BBDO in Pittsburgh, where he created ads for U.S. Steel.

In 1959, the National Society of Art Directors named Arnold Art Director of the Year, having previously bestowed its Golden T-square on such greats as Saul Bass, Charles Coiner, Walt Disney, Leo Lionni, and Bradbury Thompson. That same year, the Pittsburgh Jaycees named him Man of the Year in Art, and Arnold’s work was featured in a solo exhibition at the Carnegie Institute of Fine Arts—the first time commercial advertisements were shown there. He was also represented in a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

During the late 1950s, Arnold began doing some remarkable freelance work for several department stores, including Horne’s, Cox’s, John Wanamaker, and Higbee’s, frequently collaborating with copywriter Alan Van Dine, whom he knew from BBDO. Van Dine describes Arnold’s unusual process: “It was completely backwards. Arnold would say, ‘I want to do a watermelon.’ Or, ‘A baby carriage.’ My job was to come up with something lively to connect the visual. We didn’t know at that point which client was going to see it.”

Sometimes, Arnold would go into seclusion, and Van Dine wouldn’t hear from him for a long time. “Then I’d find an envelope of sketches at my door for me to respond to. If I couldn’t respond, I’m sure he’d have found another writer.” Their distinctive ads, which were not at all about selling merchandise, appealed to these stores’ sophisticated customers. “A lot of the ads were very funny, and some were really paintings,” Van Dine says. “I would try to write something very trenchant and stay out of the way of it.”

In 1967, in response to an assignment to create Horne’s annual Christmas newspaper ad, Arnold created a caricature of Scrooge that so captured the public imagination that the store was compelled to reprint it for sale as posters, postcards, and Christmas cards. He also designed greeting cards for the American Artist Group, many of which continue to sell. “His work seems to persist in the memory,” observes Milton Glaser, marveling at how clearly he can remember Arnold’s impeccably rendered and beautiful images. “One of the main tests of these things is their durability, and they are still very fresh, very innovative.”

Darwin Bahm, the designer’s New York agent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, said that Arnold would turn down big money in favor of a job that paid practically nothing—if he thought he could do something with it. When the Wargo family moved to Pleasant Hills, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Arnold ran a one-man agency from home, doing projects for Kodak, John Wanamaker, Sterling Drug, and other mainstream clients until retiring in the late 1970s. He continued to look after his mother until her death at age ninety-three. Arnold died in 1994.

Glaser notes that Arnold Varga remained singularly obsessed by his chosen field. The philosophy of this modest, big-boned man never varied from the answer he gave to an interviewer who asked him, at the height of his career, what set him apart from so many other artists who did not achieve his success. Arnold chose to describe, in typical understatement, what he thought made an advertisement good: “It’s informative. It’s honest. It doesn’t hurt the eye when you look at it.”

You may also like

Sunlight, Foam, and Perfect Pours: Carlsberg Like You’ve Never Seen

A simple beer has never looked this good. Jonathan Knowles, the photographer who is awarded Gold in…

Read MoreFrom Growing Minds to Urban Beats in Li Zhang’s Posters

Awarded Platinum and Gold in Graphis Poster 2026, Li Zhang moves between cultures, disciplines, and ideas, using…

Read More

Related Annuals & Publications

View AllBecome a Graphis Member

- 1-Year Membership Subscription

- Enjoy 50% off on Call for Entries

- 1-Year FREE Subscription to Graphis Journal

- Your Portfolio online with profile + links

- Get 20% off on Graphis Books